ONT read QC strategies for assembly

My colleague Hugh Cottingham recently came to me with a question about pre-assembly ONT read QC. He asked how using Filtlong with --min_length 1000 --keep_percent 95 would compare to a simpler approach like just tossing out the reads with a qscore <20. My first thought was, it probably doesn’t matter much, but I haven’t tested it. But then I thought, why not test it?

ONT read QC is a big domain with lots to potentially investigate. To keep the scope suitably narrow for this post, I tested just a few simple read subsampling/QC methods for single-assembler whole-genome assembly.1 This doesn’t precisely answer Hugh’s original question, but it does shed light on the topic, and it gives me a chance to share some miscellaneous thoughts about pre-assembly ONT read QC.

Methods

I reused the read sets from my Autocycler paper. These are five different genomes, all sequenced with ONT and basecalled with the sup@v5.0.0 model. The pre-QC read sets were very deep, ranging from 364× to 1280×. Based on this old blog post, I decided to aim for a post-QC depth of 100×.

Here are the QC methods I tried:

- none: just assembling the full read set. Not a QC method but a negative control.2

- Rasusa: random sampling to 100× depth with Rasusa. This only reduces the depth, and all other read stats (e.g. length, quality) should remain similar. So also not a QC method, more of a depth-matched negative control.

- Chopper+Rasusa: first Chopper (

-q 20 -l 1000) to discard reads with a mean qscore <20 or a length <1 kbp, then Rasusa sampling to randomly sample to 100× depth. - Filtlong-defaults: Filtlong with

--target_basesset to 100 times the genome size. This keeps the ‘best’ reads using Filtlong’s default logic which prefers longer and higher-qscore reads, so it will increase both the read length and read qscore distribution. - Filtlong-mean-qual: Filtlong with

--target_basesset to 100 times the genome size and--length_weight 0 --window_q_weight 0. This makes Filtlong only care about mean qscore, i.e. it will keep the reads with the highest quality scores. This should greatly increase the read qscore distribution but shouldn’t have much effect on the read length distribution (only to the degree that length and mean qscore are correlated).

For each of the 25 read sets (5 genomes × 5 QC methods), I assembled the reads using 11 different long-read assemblers (Canu, Flye, hifiasm, LJA, metaMDBG, miniasm, Myloasm, NECAT, NextDenovo, Raven and wtdbg2) for a total of 275 attempted assemblies.3 I then quantified their accuracy using the script from the Autocycler paper, which counts sequence-level errors and structural errors. Sequence-level errors are substitutions and small indels. Structural errors include missing bases (e.g. a missing plasmid) and extra bases (e.g. duplicated sequence at the ends of circular contigs).

Results

If you’re interested in the full results table, here’s an Excel file with everything: read_qc_results.xlsx

Read stats

| Read QC strategy | Read count | Total bases | Min read length | N50 read length | Max read length | Median read qscore |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| none | 2,956,843 | 16,884,738,340 | 5 | 9,514 | 946,320 | 21.97 |

| Rasusa | 415,227 | 2,364,203,186 | 5 | 9,603 | 544,348 | 21.90 |

| Chopper+Rasusa | 368,668 | 2,364,188,652 | 1000 | 9,583 | 98,126 | 24.14 |

| Filtlong-defaults | 90,593 | 2,364,261,194 | 10,515 | 27,455 | 128,070 | 24.05 |

| Filtlong-mean-qual | 431,507 | 2,364,193,509 | 5 | 8,808 | 104,213 | 27.69 |

The values in the above table are totals across all five genomes. As intended, all read sets except for none have about the same number of bases – the five genomes total to 23.64 Mbp, so 100× read depth is 2.364 Gbp. Since Rasusa is just random subsampling, it doesn’t change much about the read set, other than reducing its depth.4 Chopper+Rasusa increases the min read length and median qscore. Filtlong-defaults increased the median qscore and greatly increased the min and N50 read lengths. And Filtlong-mean-qual greatly increased the median qscore.

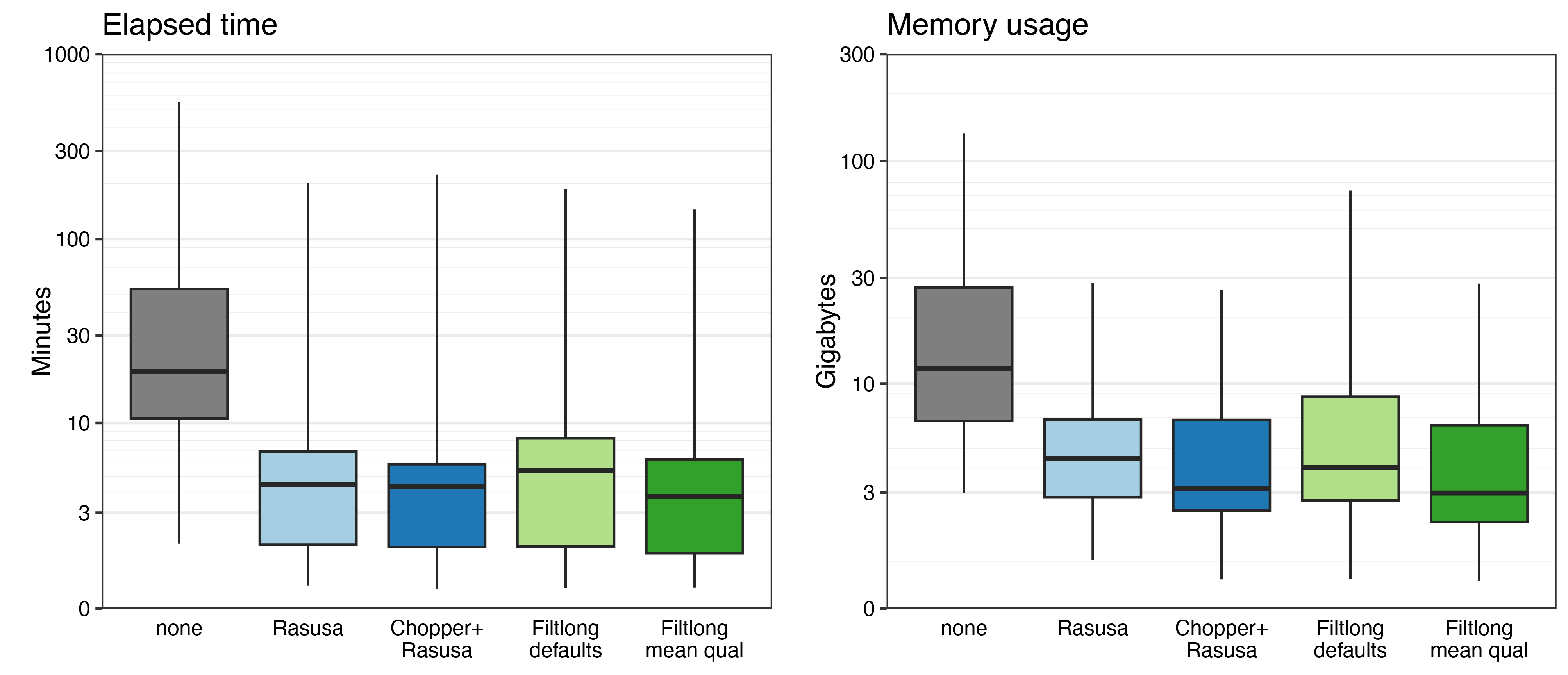

Assembly resources

As expected, the none read sets (which were very deep) took far more time and memory to assemble than the other read sets (all 100×). That’s one practical reason to do read QC.

Six of the 275 assemblies failed/crashed and did not produce a FASTA file: one Flye assembly (none) quit with a ‘No disjointigs were assembled’ error (sometimes happens when Flye is given excessively deep reads), and five LJA assemblies (four none and one Rasusa) crashed (LJA seems to struggle with very low-quality reads).

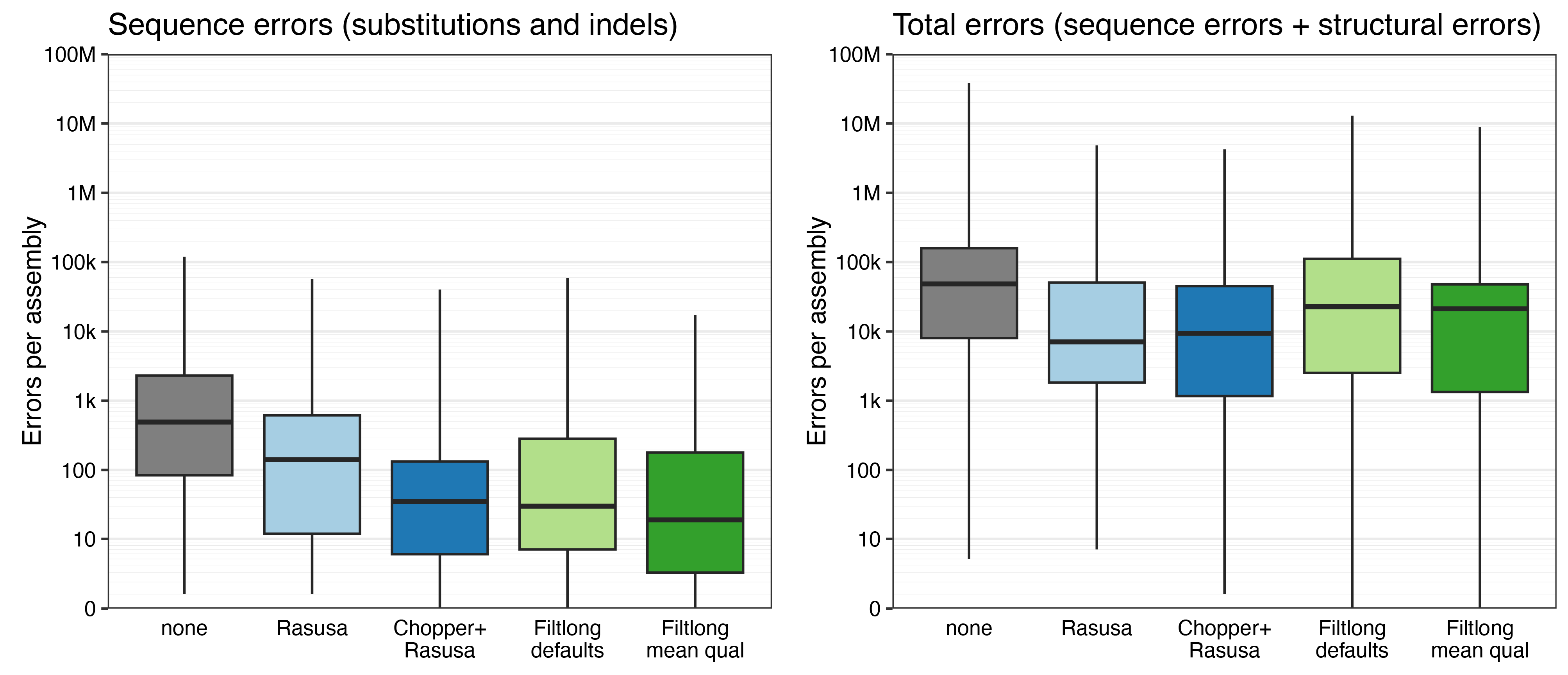

Assembly accuracy

The none assemblies were least accurate, despite the assemblers having the most information to work with. This is consistent with this post which showed that too much depth can make assemblies worse.

For the other assemblies (all 100×), the number of sequence errors (left plot) correlates with the median read qscore. The worst sequence accuracy was from Rasusa (median read qscore = 21.90, median errors per assembly = 143.5) and the best sequence accuracy was from Filtlong-mean-qual (median read qscore = 27.69, median errors per assembly = 19).

The number of total errors (right plot) didn’t show as clear of a pattern – structural errors were common with all QC methods.5 (If structural accuracy is important, you should be using Autocycler!) But Filtlong-defaults did have more structural errors because this QC approach removes small plasmids.

Discussion and conclusions

ONT read QC is a potentially huge topic, and this blog post has a narrow focus. So I’d like to explicitly state what I did not address here:

- This only tested read QC in the domain of bacterial whole-genome assembly. There are obviously a lot of other things you can do with ONT reads, and they may need different QC strategies.

- This tested the results from single assemblers (e.g. Flye). It did not look at consensus assembly, e.g. with Autocycler.

- My read sets were all very deep, so read QC was used to bring them down to a more usable depth. I did not test cases where the full read set was already a good depth (e.g. 50–100×) or a less-than-ideal depth (e.g. 20–50×).

- I only used a few tools/approaches that pass/fail on a whole-read basis. I did not look at any QC strategies that alter reads, e.g. trimming low quality bases, splitting chimeras, etc.

Given those limitations, here are the main conclusions I can draw from this mini-study:

- If you have very deep reads, definitely do some sort of QC/subsampling to bring them down to a more reasonable depth (~50-100×) before assembly. This will not just save assembly time but probably also give you better assemblies.

- Filtering by qscore definitely seems to help with sequence accuracy. This makes sense – fewer read errors mean fewer opportunities for errors to creep into the assembly. So, if you have very deep reads, I recommend including some sort of qscore-based filter.

- Filtering by length can eliminate small plasmids. Three of the five genomes I used in this study had plasmids smaller than 10 kbp, but the Filtlong-defaults QC removed all reads below 10 kbp, essentially erasing these plasmids! Be very careful using Filtlong (or any QC tool that selects for longer reads) if small plasmids are important to you.

Stepping beyond this mini-study, here are some general thoughts on the topic based on my experience:

- If your pre-QC reads are not very deep, you’ll need to be more conservative with your QC, so as to not reduce depth further. Higher pre-QC depth → more stringent QC. Lower pre-QC depth → more lenient QC. Filtlong’s

--target_basesoption can help with this. - Tossing out very short reads is probably a good idea. It can make assembly go faster by reducing the read count, especially important if the assembler contains any O(n2) algorithms. I usually use a 1 kbp threshold, since most plasmids are larger than this. If your read depth is low (so you want to preserve more depth) or you want to be extra-cautious around small plasmids (which are occasionally <1 kbp), then a 500 bp threshold might be better.

- If you are working with a tough-to-assemble genome, then a QC strategy which prefers longer reads (like Filtlong-defaults used in this post) could be beneficial. Longer reads can span longer repeats, and this can help assemblers to produce a complete assembly. Just be aware that small plasmids may be lost!

- Even when small plasmids are well represented in post-QC reads, long-read assemblers sometimes assemble them poorly or omit them entirely. So if small plasmids matter to you, I’d recommend checking out Plassembler.6

- If you have samples from a multiplexed ONT run, it’s likely that they will vary in depth.7 If you then do qscore-based filtering to a target depth (as I recommend below), you’ll create a bias in your data: samples with higher pre-QC depth will have fewer post-QC errors. If this will matter for your analysis, then random subsampling (e.g. Rasusa) could be better.

- Other QC tools do more than pass/fail whole reads. E.g. fastplong trims reads based on quality, removes adapters, splits chimeras and more. But assuming you basecalled/demultiplexed with Dorado, then most adapters and chimeras may already be taken care of. And based on this old study of mine, assemblers are pretty tolerant of untrimmed adapters and chimeras. So I suspect the extra QC steps done by fastplong probably don’t matter much for assembly, but that remains untested.

Considering all of the above, some loose recommendations for pre-assembly ONT read QC that I think would work well in most cases:

- Do some light QC to toss out very short and very low-quality reads:

chopper -q 10 -l 1000. This will clean up the worst reads and probably not reduce the overall depth by much. - If you’re going to assemble with Autocycler, then stop now! Leaving lots of depth is a good thing for Autocycler, which includes a random subsampling step in its pipeline. Read more here.

- If you’re going to assemble with a single assembler (e.g. Flye), then run Filtlong with

--target_bases "$genome_size"00 --length_weight 0 --window_q_weight 0.8 This will keep the best 100× reads as judged only by mean quality (not length). - If your assembly didn’t reach completion (e.g. the chromosome was fragmented), then you could try Filtlong with default weights:

--target_bases "$genome_size"00. This will increase the length of the post-QC reads and may help get a complete assembly. But again, be aware that you’re at risk of losing small plasmids.

Footnotes

-

By ‘single-assembler’ I mean assembling with just one tool, like Flye or Canu. This is in contrast to consensus assembly with Autocycler which uses multiple assemblers. Read QC for Autocycler would have different priorities, which I briefly address at the end of this post. ↩

-

Since the read sets used in this post came from a multiplexed ONT run, even the none reads effectively had a little bit of QC from the demultiplexing process. This is because very low-quality reads are more likely to end up in the ‘unclassified’ bin. ↩

-

I used the same approach as I did in the Autocycler paper and my last post: running the assemblers via Autocycler helper using

--min_depth_rel 0.1to clean up any low-depth contigs. ↩ -

The very long max-length reads in the none and Rasusa read sets are just junk, e.g. the

GTdinucleotide repeated over and over. This is often the case for the longest reads in a set without any QC. ↩ -

You might have noticed that ‘Total errors’ sometimes gets very high, larger than the genome size. This is because extra bases count towards total errors, and some assemblies contained a lot of extra sequence. The worst was the Klebsiella pneumoniae LJA none assembly, which was 44 Mbp in size (the genome is only 6 Mbp). ↩

-

I use Plassembler in my Autocycler pipeline specifically to help recover small plasmids. ↩

-

This seems inevitable, despite attempts at balancing things like input DNA concentration. Some barcodes just mysteriously give more yield than others. ↩

-

This assumes you know the approximate genome size, but it doesn’t need to be exact. For example, a 10% error in genome size will lead to a 10% error in target depth, so if you were aiming for 100×, you might get 90–110× (no big deal). ↩