HERRO read correction – part 1

Error-free (or close to it) sequencing reads can greatly simplify downstream analyses such as genome assembly. Therefore, long-read error correction is part of many pipelines, e.g. it’s the initial step in Canu assembly. Error correction is relatively straightforward for unique sequences in a genome: for each read, find all alignments to other reads and use the pileup to build a consensus. With sufficient read depth and a random error profile, this can yield completely error-free reads.

However, challenges arise with repeat sequences, particularly those that are almost but not quite identical.1 Using the approach I just described risks erasing minority variants in repeats, making corrected sequences identical. For example, consider the rRNA operon, the longest repeat in many bacterial genomes and often present in five or more copies. If one copy has a single-nucleotide variant, error correction could ‘fix’ reads containing the variant to match the other copies, thus erasing the variant from the genome. Not good!

HERRO is a new addition to the ONT toolkit that uses a deep neural network to boost ONT simplex reads from ~Q22 to ~Q40. Importantly, HERRO was designed to be ‘haplotype-aware’, so it aims to avoid the problem described above. Here’s a key snippet from HERRO’s paper:

Subsequently, the model selectively processes supported positions – defined as those having at least two different bases that each appear a minimum of three times - through the Transformer encoder. This encoder is designed to learn interactions between supported positions. By focusing on these challenging positions, HERRO accurately predicts the correct bases and accounts for differences between haplotypes.

If HERRO lives up to its promises, it could be a big deal, allowing ONT reads to be used in tools and pipelines designed for PacBio HiFi reads. In this post, I test HERRO, particularly focusing on the challenge of almost-identical repeats.

Methods

I used the Streptococcus pyogenes RDH275 genome from Michael Hall’s ONT variant-calling paper.2 This genome has six copies of the rRNA operon, making an exact repeat 5196 bp in length.

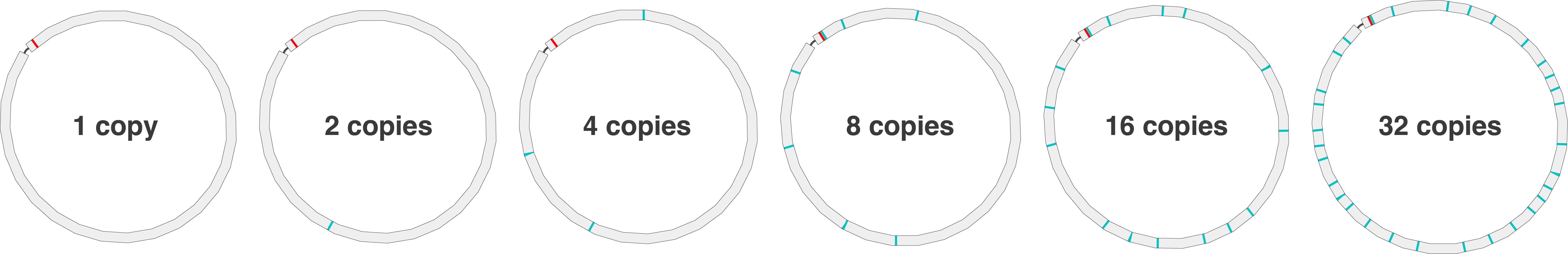

I created artificial versions of the genome with modified copy numbers of the rRNA operon: 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 32. In each, I made a single-bp change in the middle of one copy:

original: ...CGTGAGGGAAAGGTGAAAAGCACCC...

modified: ...CGTGAGGGAAAGCTGAAAAGCACCC...

*

Each genome therefore has a 5.2 kbp repeat3 (‘the repeat’) where all instances are identical except for one with a single nucleotide variant (‘the variant’). For example, in the 32-copy genome, there are 31 identical copies of the repeat (with a G in the middle) and one copy with the variant (with a C in the middle).

Here’s a Bandage illustration of the six test genomes with their rRNA operon highlighted (red for the variant copy, cyan for the original sequence):

I used Badread to create a synthetic ONT read set for each genome: 100×, mean identity of Q20, mean read length of 10 kbp, and other Badread features (adapters, junk reads, random reads, chimeras, glitches) turned off for simplicity. I call these the ‘raw reads’. I then ran HERRO (via Dorado, see Discussion) on each read set, producing error-corrected ‘HERRO reads’.

To assess accuracy, I:

- Directly examined reads covering the variant4 and counted correct (

C) vs incorrect (G) bases. - Assembled the reads with Flye and checked the accuracy of the whole genome, including the variant.

- Did a Unicycler hybrid assembly using the same file for both short (

-s) and long (-l) reads.5 This is a strange and not-recommended way to assemble a long-read set, but I did it as a comparison point because I expect it to do poorly – Unicycler is often guilty of erasing minority variants in repeats.

Results

Starting with the expected results, the raw reads of course contained the correct variant, and raw-read Flye assemblies were completely error-free6. The raw-read Unicycler assemblies, however, had errors in repeat regions and only got the variant right for the 1-copy and 2-copy genomes. With four or more copies of the repeat, Unicycler erased the minority variant.

Now for the exciting results: how did HERRO do? Excellently, I was pleased to see! The HERRO reads were usually 100% accurate and always contained the correct variant base (C), and the HERRO-read Flye assemblies were completely error-free. So even in the case of a 32-copy repeat with a variant in one copy, HERRO correctly maintained the variant. The HERRO-read Unicycler assemblies erased the variant in 4-copy and higher genomes, but this was a failure of Unicycler not HERRO.

Discussion and conclusions

This test was quite limited in scope, but the results are encouraging. If HERRO behaves well with an extreme case (32 rRNA operons), I feel good about its performance on more realistic cases. But while this synthetic test demonstrated that HERRO reads could produce good assemblies, it didn’t show whether HERRO reads produce better assemblies – after all, my raw-read Flye assemblies were also error-free. I.e. is there any benefit to doing error correction at the read level when the assembler is also doing it at the consensus level? To answer that, more robust benchmarking of long-read assembly methods using real reads is needed. I have plans for that, so stayed tuned!

While I was impressed by HERRO, it has some limitations. It operates on 4096-bp chunks of sequence, so reads shorter than that are excluded from its output. This could be problematic for bacterial genomes with small plasmids (which are often <4 kbp) or any read set with a poor N50. Another limitation is that HERRO’s reads are in FASTA format, not FASTQ. While many tools (such as Flye) will take FASTA as input, others (such as Unicycler) do not. This is surmountable, as a FASTA file can be converted to FASTQ with dummy qscores, but native FASTQ output with informative qscores would be better.

Usability is another issue. Installing and running HERRO is complex, and I was not able to make it work. The conda recipe needed modifications, the Singularity image download link didn’t work, and compiling from source failed due to C++ version issues.7 Thankfully, ONT has integrated HERRO into Dorado via the dorado correct subcommand, so that is what I used.8 It has a simple one-step CLI: just specify the model and input reads, and it outputs the corrected reads to stdout.

Final thought: in this post, I looked at a ~5 kbp repeat using ~10 kbp reads, i.e. my reads were longer than the repeat. I did not assess how HERRO performs in the tougher case where the repeat is longer than the reads. I will tackle this in a follow-up post. To be continued…

Footnotes

-

I usually work with haploid bacterial genomes, where repeats make up a relatively small proportion of the genome. In diploid/polyploid genomes, however, you could consider the entire genome to be an almost-but-not-quite-identical repeat! ↩

-

I used this genome because I had a nice assembly on hand, it’s not too large (saves some computational time) and its rRNA operon seems to be an exact 6× repeat. Also to promote Michael’s great paper

↩

↩ -

In the genome with just one copy of ‘the repeat’, it’s not actually a repeat at all, and ‘the variant’ is the only version of the sequence. This serves as a simple control – HERRO should certainly get this one right. ↩

-

Badread includes the genomic coordinates of each read in the FASTA header. This made it easy for me to reliably find the reads which span the variant. ↩

-

I first tried using ONT reads as ‘short reads’ for Unicycler a couple years ago. It works because ONT read accuracy is now almost as good as Illumina read accuracy. While it’s probably a bad idea to do this for an entire bacterial genome, it can be useful with small plasmids (which long-read assemblers often botch), a fact exploited by George Bouras in Plassembler. ↩

-

A few Flye assemblies didn’t quite get the contig circularisation correct, creating a duplicated base at the start-end of the contig, but I’m not counting that as an error for the sake of this experiment. ↩

-

Libtorch requires C++17, but for reasons I could not figure out, my build kept adding the

-std=c++14flag which resulted in errors. ↩ -

This makes me wonder: who will take ownership of HERRO going forward? Dominik Stanojević, the original developer? Or will ONT pick up the baton? Or both in parallel? ↩