Duplex basecalling for whole-genome assembly

Sometimes during ONT sequencing, after one strand of DNA finishes its trip through a pore, the other strand immediately follows, and there are two different ways that the basecaller can handle this. It can make a separate read from each strand’s signal, what ONT calls simplex sequencing. Or it can basecall both signals together to make a single read with higher accuracy, what ONT calls duplex sequencing. In my experience, about 15–20% of ONT read signals are part of a duplex pair.1

So there are two approaches2 one might use to basecall ONT sequencing runs:

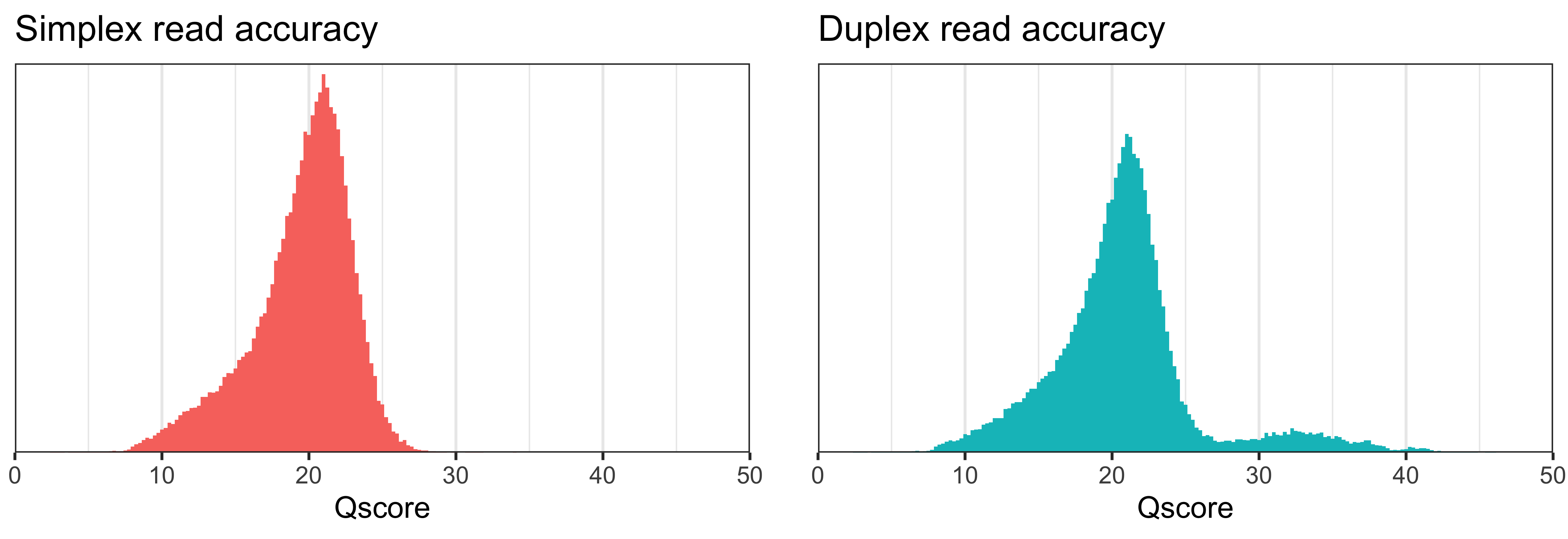

- Simplex basecalling: Each signal is basecalled separately, whether or not it is part of a duplex pair. E.g. 1M read signals will generate 1M basecalled reads, and the read accuracy distribution will be monomodal.

- Duplex basecalling: Signals that are part of a duplex pair are basecalled together into duplex reads, and signals not part of a duplex pair are basecalled as simplex reads. E.g. 1M read signals with a duplex rate of 20% would generate 100k duplex reads and 800k simplex reads3, and the read accuracy distribution will be bimodal.

High read-level accuracy is nice, but I work in genome assembly so mainly care about consensus-level accuracy. Which of the two approaches is better for that? If I have 100× ONT data with a 20% duplex rate, I could basecall with option 1, generating an average of 100 simplex reads for each position of the genome which are then used to make the consensus. Or I could basecall with option 2, generating an average of 80 simplex reads and 10 duplex reads for each point in the genome which are used to make the consensus.

In both scenarios, all of the reads ultimately contribute to the consensus sequence (whether or not they are first pairwise combined into duplex reads), so option 2 seems like it might be unnecessarily complicated. For this reason, I’ve been somewhat dismissive of duplex sequencing in the context of bacterial genome assembly. However, I recently saw a talk by Chiara Crestani where she used ONT sequencing for typing pathogens, and she did see a benefit from using duplex basecalling.4 That made me reconsider, and it inspired this blog post where I compare the two approaches.

Methods

For this test, I used three strains from Michael Hall’s ONT variant-calling paper5. Each has a good ONT read set and an Illumina-polished curated assembly to use as ground truth:

I basecalled each strain’s pod5s using dorado duplex and subsampled the results to different depths: 20–80× at 5× intervals6. I then made a simplex and duplex version of each read set:

- Simplex means basecalling approach 1. I made this by excluding any reads in Dorado’s BAM file with a

dx:i:1tag. - Duplex means basecalling approach 2. I made this by excluding any reads in Dorado’s BAM file with a

dx:i:-1tag. While I refer to these read sets as ‘duplex’ for brevity, they contain a mixture of both simplex and duplex reads, with about 9% of the reads being duplex.7

I then assembled each read set using my usual set of assemblers: Canu, Flye, miniasm+Minipolish, NECAT, NextDenovo+NextPolish and Raven.8 Finally, I used Trycycler to combine these six alternative assemblies into a single (usually better) assembly.9

3 strains × 13 depth intervals × 7 assemblers × 2 basecalling methods = 546 assemblies in total

To count assembly errors, I used compare_assemblies.py to do a global alignment of each assembly’s chromosomal contig to the ground-truth chromosome.10

Results

These histograms show how the simplex and duplex read sets have monomodal and bimodal accuracy distributions, respectively:11

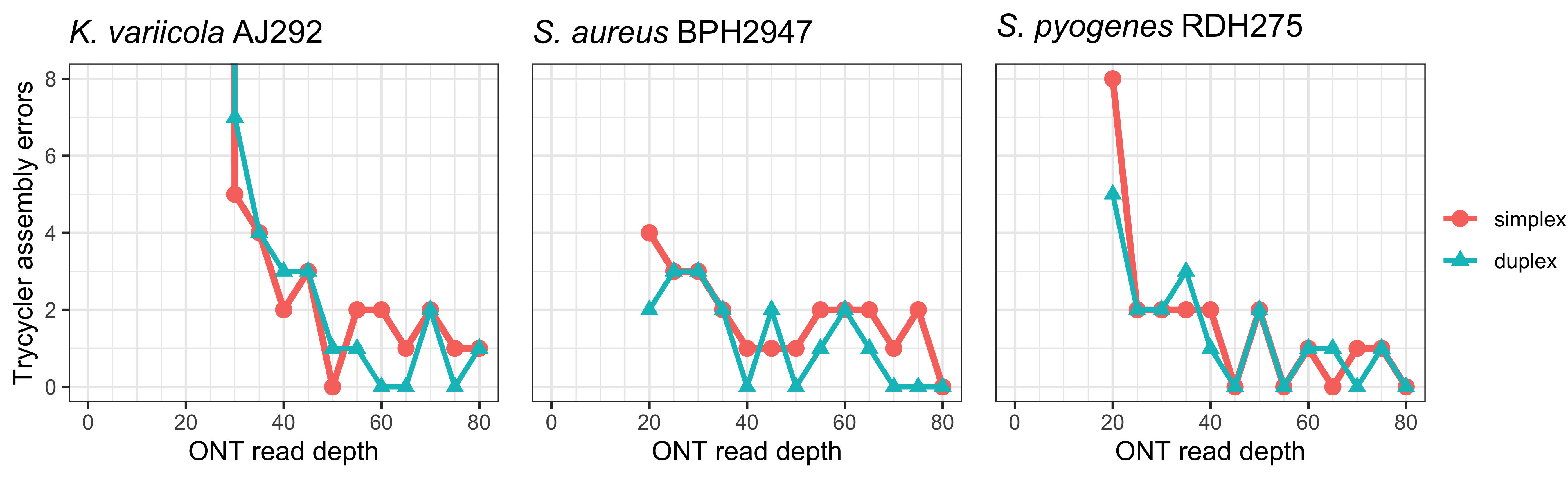

The Trycycler assemblies usually had less than 10 errors.12 These plots show remaining errors vs read depth for each strain:

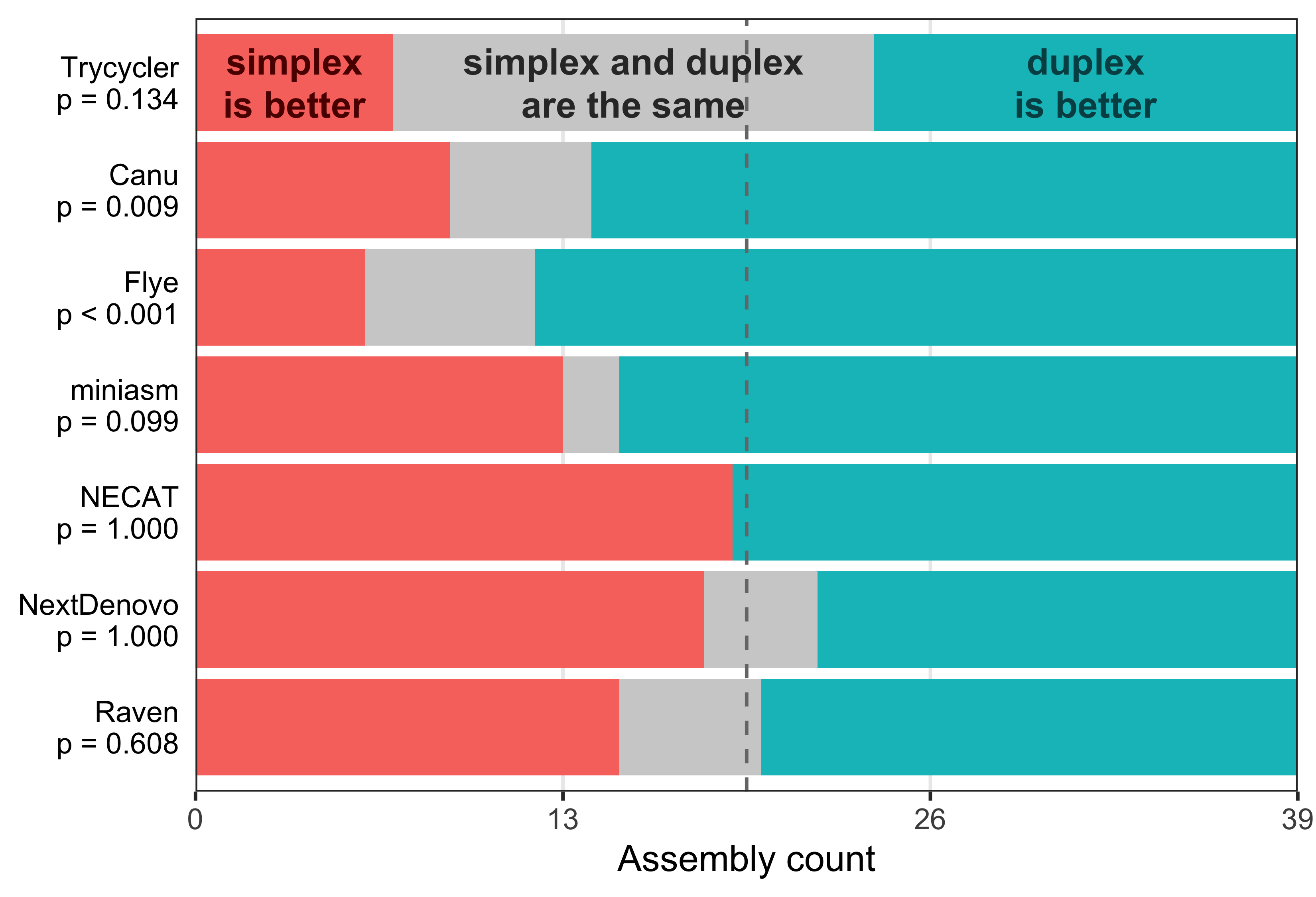

For each of the assemblers, I counted how often the simplex or duplex assembly had a lower error count. Each assembler has a p-value from a two-tailed binomial test comparing simplex-is-better counts to duplex-is-better counts (ignoring the ties):

If you’d like to look at the full table of assembly accuracy results, you can download it here: duplex_results.tsv.

Discussion and conclusions

For most of the assemblers, duplex reads usually delivered assemblies with fewer errors. The p-values weren’t particularly impressive, but the result was strong for Flye (the assembler I use most). I was also happy to see that each of the strains could sometimes assemble with zero errors. Most often, these perfect assemblies came from Trycycler and duplex read sets. So overall, duplex basecalling for assembly looks good!

These results are enough to make me tentatively recommend using duplex basecalling when possible. However, at the time of writing, dorado duplex is missing some key features: it cannot demultiplex or trim adapters/barcodes. These features are sorely missed for bacterial WGS runs which are usually barcoded, so I hope they are added in future versions of Dorado.

This blog post only scratches the surface – I still have lots of questions about duplex basecalling in the context of assembly. Exactly why do duplex reads seem to help with assembly accuracy? Perhaps they are better at getting homopolymers right, a common source of ONT consensus errors. Perhaps they help solve strand-specific errors, tipping the consensus to the correct sequence.13 Do higher duplex rates further improve accuracy? I also wonder if tools might benefit from being duplex-aware, e.g. an assembler that could recognise duplex reads and give them more weight in its consensus algorithm.

May 2025 update

I’ve recently heard that ONT is deprecating duplex basecalling – not surprising given their recent silence on the topic. This is now the third time (after 2D and 1D2) that ONT has tried and dropped both-strand basecalling! So it seems that mixed simplex-duplex read sets like the ones in this post will end up a historical curiosity rather than a standard part of ONT sequencing.

Footnotes

-

This is known as the duplex rate. Higher duplex rates can be achieved by optimising the prep and the molarity of the DNA loaded onto the flowcell. ONT has documentation with specific advice. ↩

-

There are other possibilities as well. You could discard any signals not part of a duplex pair to get a duplex-only read set. While this might be beneficial for analyses that depend on read accuracy, it involves discarding much of your data, so I’m not considering that option here. Or you could basecall all signals as simplex reads and then additionally basecall duplex pairs as duplex reads. This seems redundant (keeping both simplex and duplex versions of a duplex pair), so I’m not considering that option either. ↩

-

The calculation can be confusing: if the duplex rate is r, the proportion of duplex reads should be about r/(2-r). See this discussion on GitHub. ↩

-

Here is a brief summary of Chiara’s results, in her own words:

In a study utilising Nanopore R10.4.1 sequencing with a rapid barcoding kit, data was basecalled with Guppy and Dorado Duplex (DD), and assembled with Flye. Duplex reads constituted 10.4–14% of the total. For seven Klebsiella isolates, the average cgMLST mismatches ranged from 10 (20×) to 3 (>90×) with Guppy, and 3 (20×) to 1 (>40×) with DD. For seven Corynebacterium spp. isolates, mismatches averaged from 68 (20×) to 25 (60×) with Guppy, and 17 (20×) to 4 (>60×) with DD. Notably, Klebsiella variicola subsp. variicola and Corynebacterium rouxii exhibited more mismatches: 55 (20×) to 26 (90×) with Guppy and 27 (20×) to 23 (90×) with DD for the former; 737 (20×) to 562 (>80×) with Guppy and 241 (20×) to 131 (>80×) with DD for the latter, with a potential species effect due to methylation yet to be confirmed. Among eight Bordetella spp. isolates, mismatches ranged from 24 (20×) to 4 (>60×) with Guppy and 6 (20×) to 3 (>40×) with DD. ↩ -

The paper used 14 strains in total. I excluded the eight ATCC strains because I’ve used them in many previous blog posts and wanted to try something different. I excluded K. pneumoniae KPC2 because it’s the lower depth of the two Klebsiella isolates. I excluded S. dysgalactiae MMC234 because it’s the lower depth of the two Streptococcus isolates and it had a tricky extra-long homopolymer which makes me less confident in the ground-truth assembly. And I excluded Mycobacterium tuberculosis AMtb_1 because it was harder to assemble (a lot of the assemblies failed to complete). This left me with the three strains described above. ↩

-

I didn’t go below 20× because lower depths are less likely to successfully assemble. And I didn’t exceed 80× because the lowest-depth isolate (Klebsiella variicola AJ292) only had 96× depth in total. ↩

-

Since each duplex read is made from two simplex reads, the duplex read sets are actually a bit shallower than the simplex read sets. As a toy example, consider a simplex read set with five reads:

a,b,c,dande. If readsbandcform a duplex pair, then the duplex read set will only have four reads:a,bc,dande. When I report read depths, I’m reporting the simplex depth. For example, the 40× simplex read set for Klebsiella variicola AJ292 is actually 40×, but the 40× duplex read set for Klebsiella variicola AJ292 is ~37×. ↩ -

Long-read assemblers often make mistakes around the contig ends, e.g. duplicated sequence due to start-end overlap. Since I wanted this experiment to compare base-level accuracy, not large-scale structural accuracy, I manually repaired these errors whenever I could. This usually meant trimming some sequence so contigs circularised cleanly. ↩

-

Trycycler can often be a lot of work, but these were pretty easy because my three strains were all easy to assemble, and I only looked at the chromosome (so I just needed to grab the top cluster for each). Only a few Trycycler assemblies needed manual intervention to complete. ↩

-

The Klebsiella and Streptococcus strains don’t have any plasmids. The Staphylococcus strain has two plasmids (27 kbp and 3 kbp), but I ignored those when counting errors. ↩

-

I made these histograms by aligning the reads to the ground truth genome and counting the errors, not by looking at the quality scores in the FASTQ files. While FASTQ quality scores are pretty well correlated with read accuracy, they can’t be trusted in an absolute sense. ↩

-

The Klebsiella variicola AJ292 assemblies struggled with some misassemblies at low depths, sometimes resulting in hundreds or thousands of errors in the Trycycler assembly, so those points are cropped off the top of the plot. ↩

-

To illustrate this hypothesis, imagine a location of the genome where simplex reads always make an error on one strand (perhaps due to a DNA modification) but not on the other. This would lead to about 50:50 reads being correct vs not, so the error might end up in the consensus. But if duplex reads could always get the sequence right, they might skew the ratio (e.g. to 55:45) so the consensus sequence is more likely to be correct. ↩