Dead-end count for QC of short-read assemblies

Introduction

When I’m working with large numbers of short-read bacterial genome assemblies, I often need to do a bit of quality control (QC) before my analysis. For example, if I had 1000 Illumina read sets for bacterial whole genomes and assembled them using Unicycler1, some of the assemblies may be quite poor (e.g. due to insufficient read depth) and I’d like to exclude them.

Common assembly metrics include total size, contig count (fewer is better) and N50 contig length2 (longer is better). The problem with these metrics is that ‘good’ or ‘bad’ values are highly dependent on the species. So as an alternative/additional metric, I like to use the number of dead ends in the assembly graph (fewer is better), which captures assembly quality in a species-agnostic way. This works well because most bacterial replicons are circular, and the DNA itself has no dead ends. So if all goes well with assembly, the contigs should also have no dead ends, i.e. every contig should lead into another via links in the graph. It doesn’t always work perfectly – good assembly graphs sometimes have a few dead ends. But if an assembly has a lot of dead ends, that’s a red flag.

Example

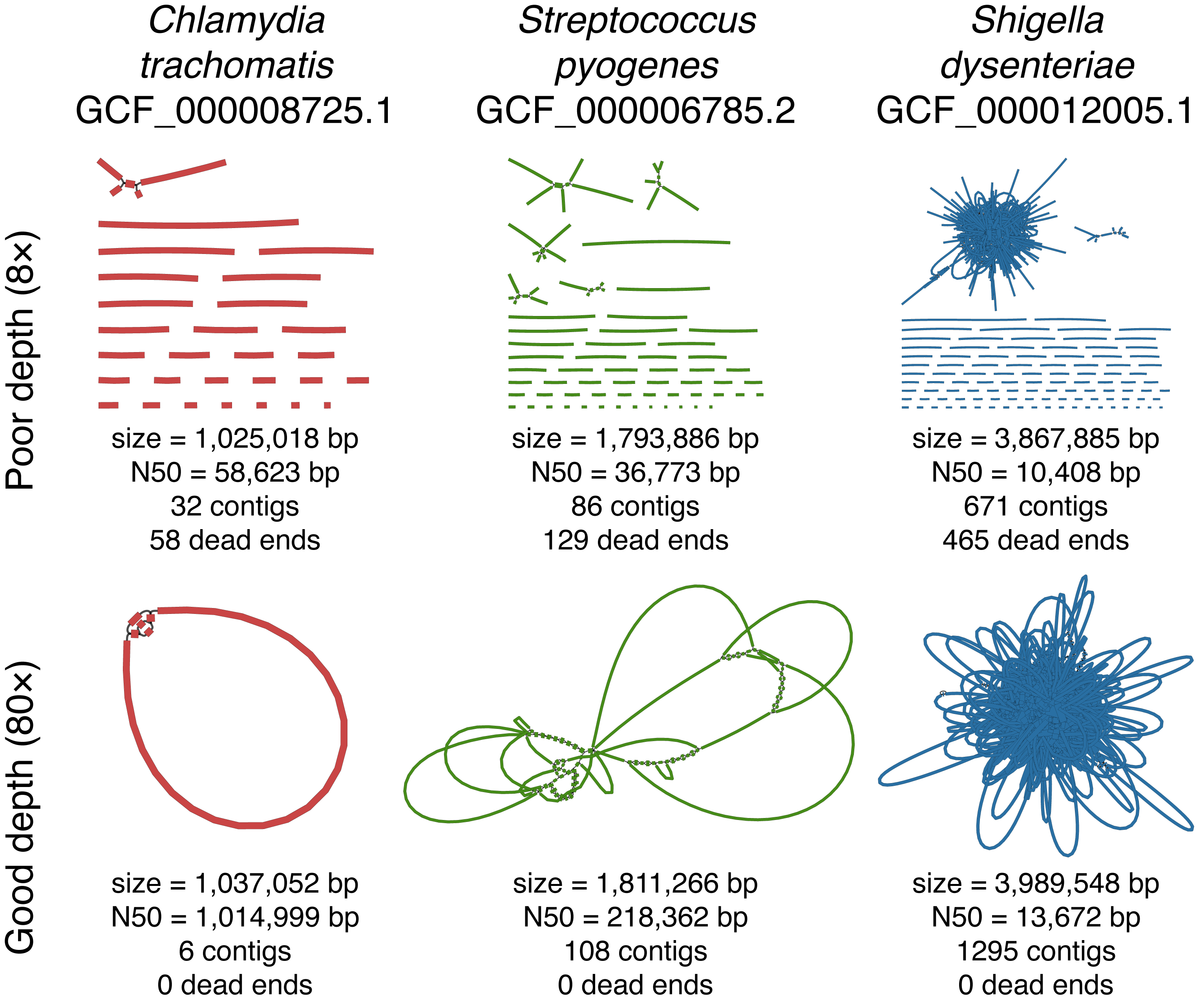

Here I took three genomes of varying complexity and assembled each with poor read depth (top row) and good read depth (bottom row) using simulated reads3. The Chlamydia genome is very simple (few repeats), the Streptococcus genome has intermediate complexity, and the Shigella genome is quite complex (hundreds of insertion sequences).

As you can see, a good N50 value is highly dependent on the species, e.g. the bad N50 for Chlamydia (59 kbp) is much larger than the good N50 for Shigella (14 kbp). However, each of the good assemblies has no dead ends, and each of the bad assemblies has a lot.

Tools

gfastats is a tool that can report graph information, and you can grep for the dead-end count:

gfastats assembly.gfa | grep "dead ends" | grep -oP "\d+"

Bandage (or the active fork BandageNG) can be run on the command line to give some assembly graph information, and you can grep for the dead-end count:

Bandage info assembly.gfa | grep "Dead ends" | grep -oP "\d+"

If you have Unicycler installed for your Python instance, you can run this Python one-liner to get the dead-end count:

python3 -c "import sys; import unicycler.assembly_graph; print(unicycler.assembly_graph.AssemblyGraph(sys.argv[1], 0).total_dead_end_count())" assembly.gfa

GFA-dead-end-counter

While the above options all work, I wasn’t completely satisfied with any of them. gfastats randomly hangs indefinitely (~1/20 times I run it on my MacBook and ~1/200 times I run it on my Linux server), making it inconvenient to run on large datasets. Bandage is primarily a GUI program and can be awkward to run on servers. And Unicycler requires an ugly Python one-liner.

So I decided to write a dedicated GFA dead-end counting tool: GFA-dead-end-counter. It’s very fast because it’s written in Rust and only does one thing (count dead ends).

Run it like this:

deadends assembly.gfa

Performance

I tested each of the tools on a medium-sized (40 Mbp, 22k segments, 10k links) metagenome assembly graph:

| Program | Dead ends | Time (s) | Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gfastats | 29312 | 0.77 | 77 |

| Bandage | 29312 | 1.17 | 226 |

| BandageNG | 29312 | 0.34 | 60 |

| Unicycler | 29312 | 2.82 | 131 |

| GFA-dead-end-counter | 29312 | 0.02 | 7 |

And on a big (396 Mbp, 697k segments, 683k links) metagenome assembly graph:

| Program | Dead ends | Time (s) | Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| gfastats | crashed | crashed | crashed |

| Bandage | 394340 | 27.28 | 1907 |

| BandageNG | 394340 | 4.82 | 567 |

| Unicycler | 394340 | 31.88 | 1528 |

| GFA-dead-end-counter | 394340 | 0.52 | 202 |

Importantly, all tools agreed on the number of dead ends! BandageNG is faster than Bandage due to improved GFA parsing in that fork. Unicycler is slow because it’s in Python. In addition to the random hangs mentioned above, gfastats crashed on the big assembly graph. GFA-dead-end-counter was by far the fastest, but it only reports dead ends (no other stats).

Recommendations

If you have a lot of assemblies to QC, especially if there are multiple different species in your set, I recommend including dead-end-count as one of your QC metrics4. This will help catch assemblies that are suffering from poor read depth or low-level contamination5. It’s hard to say the exact number of dead ends which separates a ‘good’ assembly from a ‘bad’ one, so I recommend plotting a histogram to help put the threshold in a natural place.

One assembly problem that dead-end-count does not reliably catch is high-level contamination, e.g. a 50:50 mixture of two genomes in a single read set6. For this reason, it’s also a good idea to have a maximum total size threshold (easier for a single-species dataset than a mixed-species dataset).

It’s also worth noting that dead-end-count is probably not a good QC metric for short-read metagenome assemblies. This is because many metagenomes have low-abundance organisms which will be fragmented in the assembly graph. So even with a good read set, large numbers of dead ends are probably inevitable (see my performance tests above).

References

Footnotes

-

While Unicycler is better known as a hybrid (short+long) assembler, it can do short-read-only assembly as well. In this mode, it does lots of assemblies with SPAdes using a wide k-mer spread, chooses the best assembly, then performs some graph clean-up like trimming of overlaps. You can think of short-read-only Unicycler as SPAdes plus a few bells and whistles. ↩

-

N50 length is defined as the length where all contigs of this size and larger make up at least half the total bases in the assembly. It can be calculated by sorting contigs from large to small and doing a cumulative sum until you reach half the assembly size – the size of the contig which gets you over this threshold is the assembly N50. It can be more useful than mean contig size because it’s not as affected by small contigs. For example, adding 100 tiny contigs to an assembly will greatly reduce the mean contig size but will have little effect on the N50. ↩

-

The assembly graphs were visualised with Bandage which allows for a subjective assembly assessment. High-dead-end assemblies are chopped up, resulting in many separated components in the graph. ↩

-

You’ll need to keep the graph version of your assemblies to count dead ends – FASTA assemblies won’t work. For SPAdes, the file is called

assembly_graph_with_scaffolds.gfa. For Unicycler, the file is calledassembly.gfa. ↩ -

Unicycler automatically removes low-depth contigs (adjustable via

--depth_filter). So if you used Unicycler, low-level contamination is probably not an issue. ↩ -

High-level contamination may not produce dead ends because the contaminant genome is sufficiently high depth to assemble completely. ↩