Oxford Nanopore accuracy vs depth

Introduction

This post shows the results of a mini-study I did examining the effect of Nanopore read depth on sequence accuracy. It should help with the common question of ‘How deep should I sequence?’

The inspiration for this was a particularly deep whole-genome Nanopore sequencing run we (the Holt Lab, in particular Louise and Kelly) did on a Klebsiella isolate. The resulting reads were long (N50 of ~40 kbp) and very deep (about 800×), and therefore provided a nice opportunity to experiment with assemblies of varying depth.

Note that this analysis did not aim to study assembly completeness, i.e. how likely you are to get your chromosome assembled into a single contig. That would depend on read depth, read length and the number/size of repeats in the genome. Instead, the focus here is only on sequence accuracy, i.e. the rate of errors in the assembled sequence. Assuming your reads are long enough (longer than the longest repeat in the genome), then sequence accuracy should depend mainly on read depth.

Methods and results

Flye and Flye+Medaka

The Nanopore reads were from an R9.4.1 flow cell, and I basecalled them with Guppy v5.0.7 using the super accuracy model. I produced a reference assembly for this genome using all available Nanopore reads and then polished it with Illumina reads from the same isolate. This went well (with one complication, see the appendix), and I treated this reference assembly as 100% accurate.

I then used seqtk to produce 400 random subsamples of my reads with depths ranging from 0× to 400× (uniformly spaced on a square-root scale). Each read subset was assembled with Flye v2.8.3, the chromosome was extracted and rotated to a consistent starting position, and then the assembly was polished with Medaka v1.4.1. For each assembly (both before and after Medaka polishing), I did a global alignment to my reference chromosome and quantified the accuracy using BLAST identity.

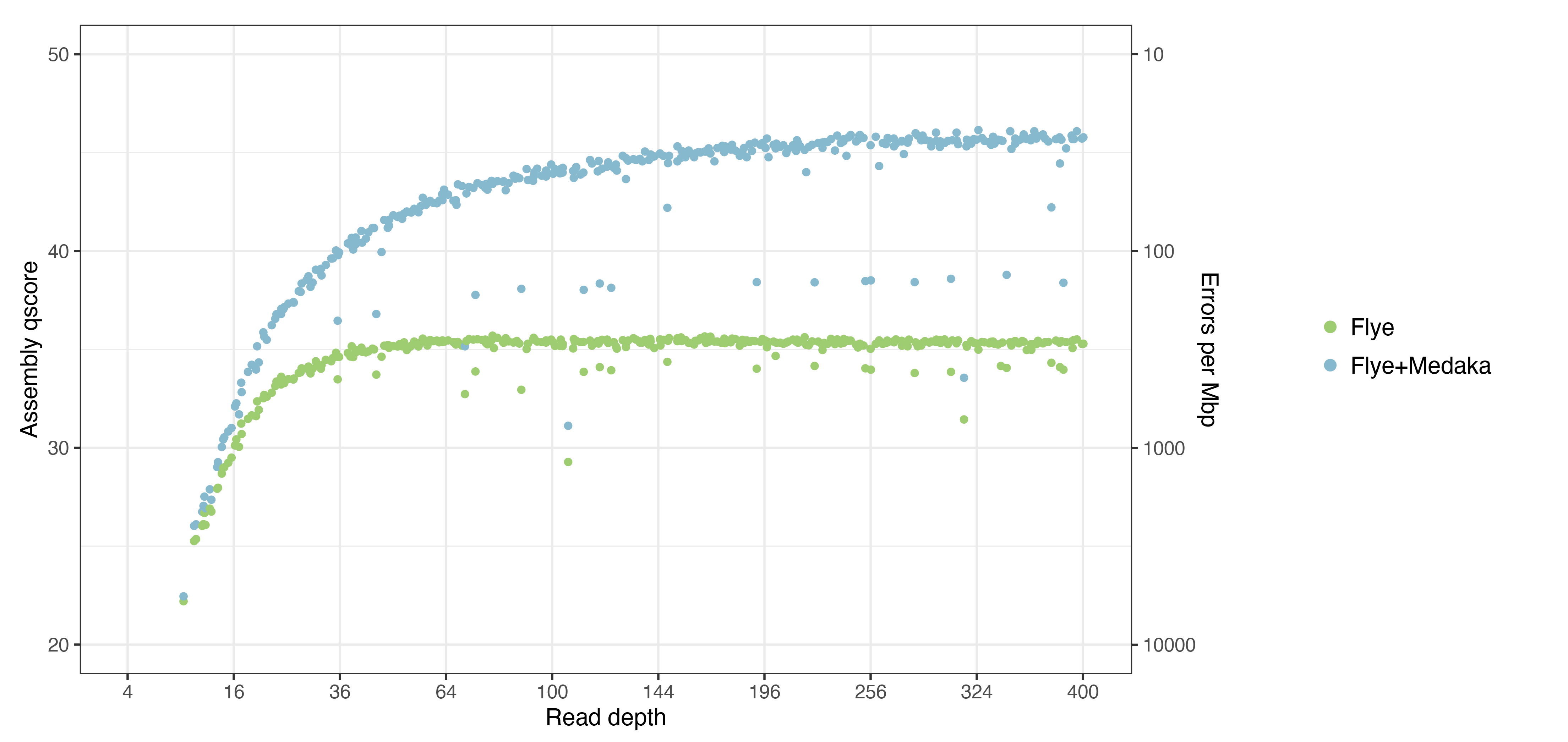

Here are the results, with accuracy plotted as qscores:

Lots of interesting things to note:

- Flye was an incredibly reliable assembler! It only failed to produce a complete chromosomal contig when read depth was ~10× or less. I’m sure this was helped by the large read N50 and the relative simplicity of the genome (it had no big repeats), but it reinforces my opinion that Flye is the best assembler for bacterial genomes.

- The accuracy of Flye assemblies maxed out at ~Q35.5, and it reached this accuracy at a depth of ~50×. So very high read depths did not improve Flye assembly accuracy.

- The accuracy of Flye+Medaka assemblies maxed out at ~Q46, and it reached this accuracy at a depth of ~250×. So very high depths are beneficial when polishing with Medaka.

- I was impressed by Medaka’s performance: given sufficient read depth, it could fix about 90% of the errors in a Flye assembly. Also, Medaka only ever made an assembly better, never worse, even at low read depths.

- Some of the assemblies fell considerably below the main curve. This occurred in about 5–10% of the assemblies, depending on where you draw the line. These assemblies had larger-scale errors, significantly impacting their overall qscore.

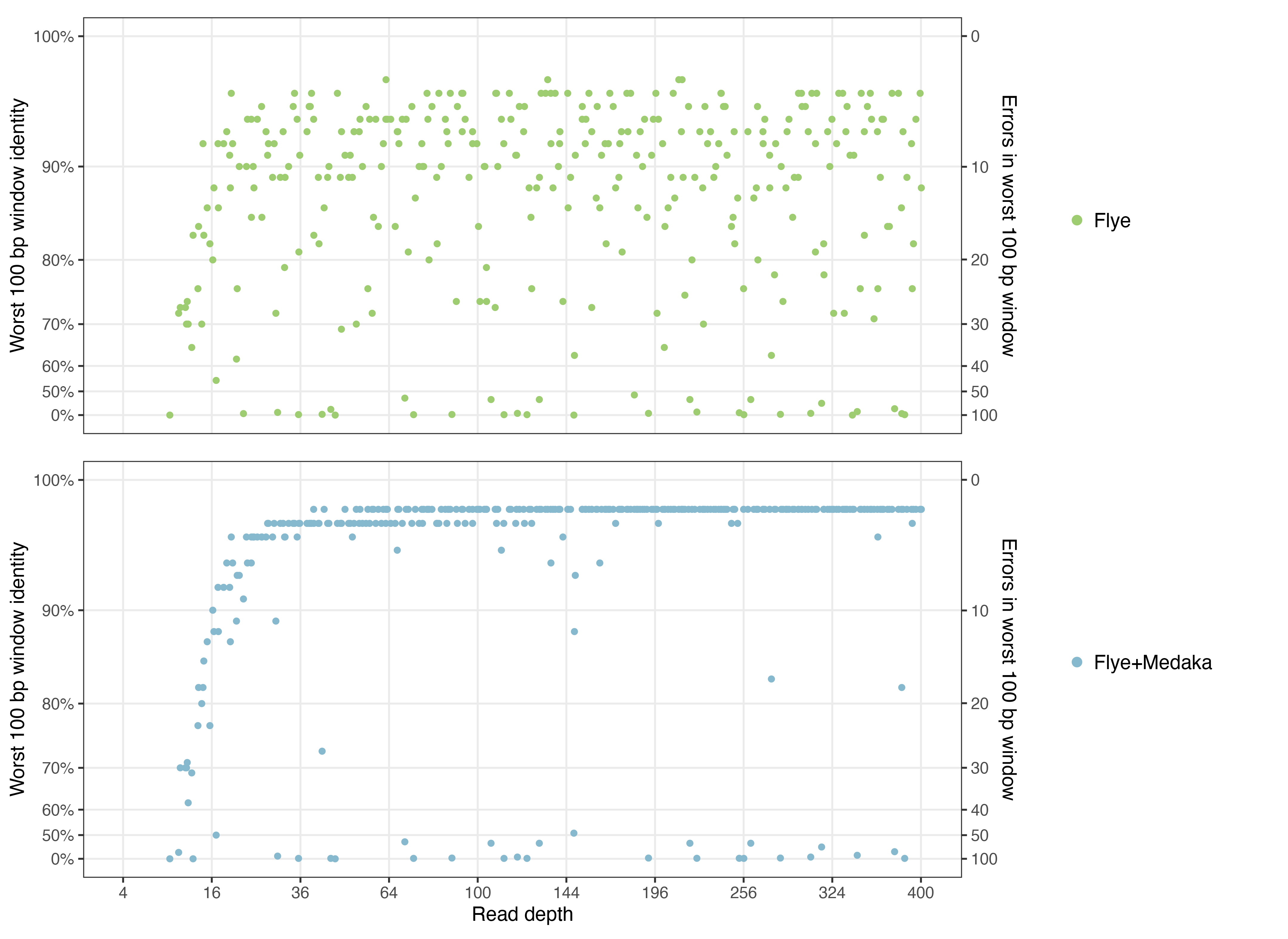

Another way I like to look at accuracy is the worst-100-bp identity, i.e. the minimum identity from a 100-bp sliding window over the assembly-to-reference alignment. This shows how bad an assembly is at its worst point, allowing one to distinguish assemblies which are uniformly good from those with local problems/misassemblies. Here are those values plotted:

Things to note:

- Assemblies with a worst-100-bp identity over 90% are pretty good. Those from 80–90% are mediocre. And anything below 80% is bad.

- Flye assemblies span the entire range of worst-100-bp identities. Medaka assemblies, in contrast, tend to cluster at the top or the bottom.

- This shows that Medaka can reliably fix not-too-big errors in a Flye assembly. E.g. Medaka can probably fix a 15-bp deletion (which would result in worst-100-bp identity of 85%). But if the error is too large (e.g. a 500-bp deletion), then Medaka cannot fix it.

- High depth assemblies suffer from poor worst-100-bp identities at about the same rate as lower depth assemblies. So increased read depth does not protect against medium-to-large scale assembly errors.

Trycycler and Trycycler+Medaka

I also wanted to test Trycycler in a similar manner, but Trycycler assemblies take a bit more work – unlike Flye assemblies, they are not fully automated. I did not have the time to assemble all 400 read subsets with Trycycler! Instead, I performed 15 Trycycler assemblies (following the How to run Trycycler instructions), ranging from 36× to 400× depth. These were then polished with Medaka and assessed in the same way as the Flye assemblies.

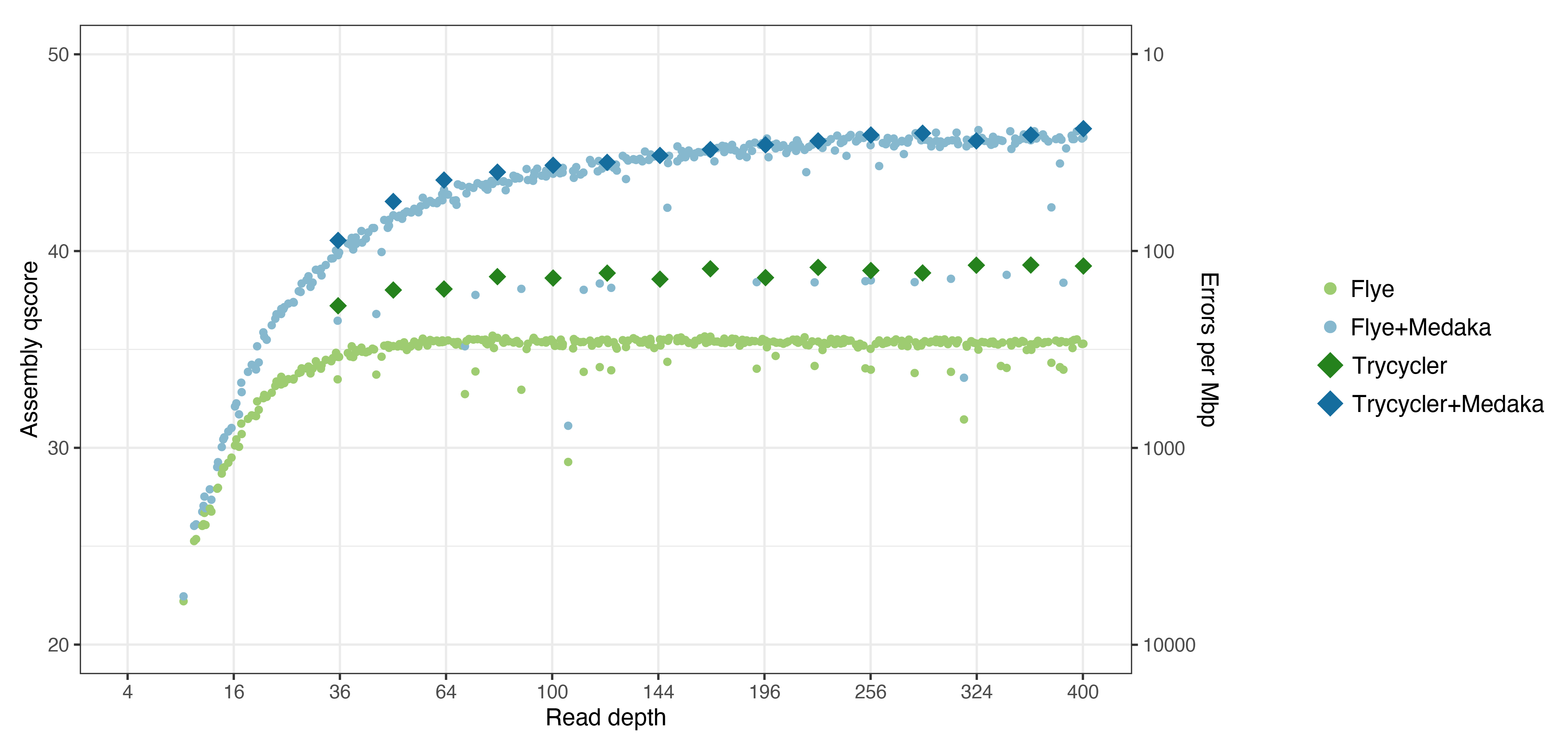

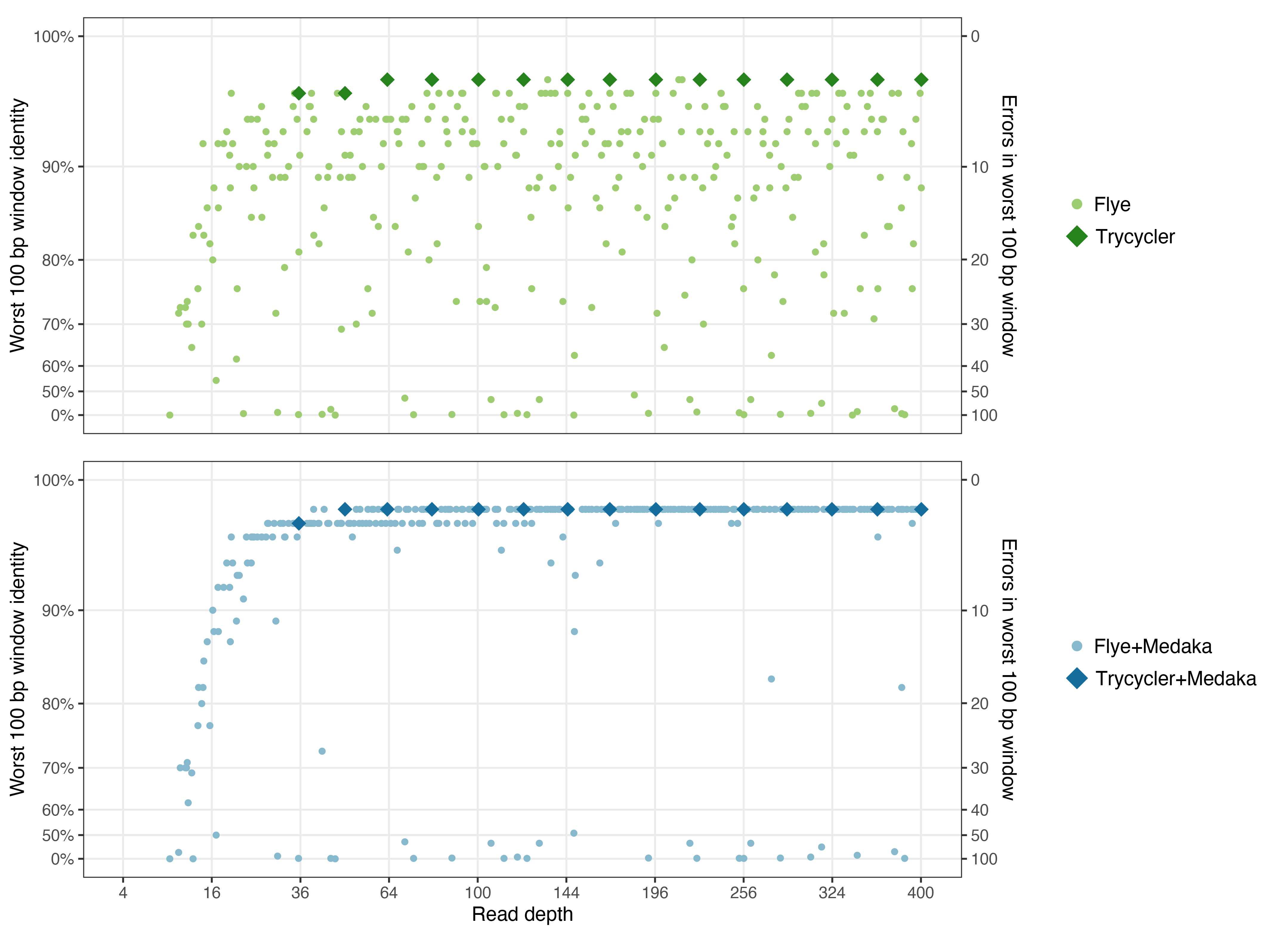

Here are the same plots shown above, now with Trycycler and Trycycler+Medaka points added:

Interesting things:

- Trycycler gave a huge accuracy boost over Flye: ~Q39 vs ~Q35.5. This equates to about half the total number of errors. This is because of the multi-assembler input used by Trycycler (Flye, Miniasm+Minipolish and Raven, see Generating assemblies). I tried making a couple Trycycler assemblies using only Flye assemblies as input, and this boost went away.

- Trycycler+Medaka assemblies don’t have much of an accuracy advantage over a good Flye+Medaka assembly. I.e. assuming there isn’t a big error which Medaka can’t fix, a Medaka-polished assembly is equivalently good whether the input was from Flye or Trycycler.

- Trycycler assemblies reliably have a very good worst-100-bp identity. This is one of the main things Trycycler was designed to do, so I was happy to see this result!

Conclusions

This analysis only used a single genome, and the specific accuracy values (~Q35.5 for Flye, ~Q39 for Trycycler, ~Q46 for Medaka) may not translate to other genomes. Most of the remaining errors are homopolymer-length errors, and so the number/size of homopolymers in your genome will influence the overall sequence identity you can achieve. But I predict that the shape of the accuracy curves would look similar for other genomes, even if they level off at different identities. The basecalling model and pore type will also affect identity: smaller/faster Guppy models (fast or high-acc) would almost certainly give lower identities, and an R10.3 flow cell would almost certainly give higher identities.

Here are the generalisable conclusions I draw from this mini-study:

- Anything less than 10× Nanopore read depth will probably not assemble well.

- From 10× to 25× depth, a completed assembly may be possible, provided your read length is good enough. But the accuracy won’t be great.

- 25× or more depth is probably enough to give you a decent assembly, again assuming good read length. But 50× is better.

- Running Medaka on a Nanopore assembly is always a good idea!

- If you want to maximise the accuracy of your Medaka-polished Nanopore assembly, then up to 250× depth might be beneficial.

- Flye assemblies are usually pretty good, but they can suffer from larger-scale errors, even when read depth is high. Medaka can fix these errors if they aren’t too big.

- Trycycler helps to avoid larger-scale errors in the assembly. Flye assemblies had a 5–10% chance of producing an error too large for Medaka to fix, but this did not occur in any of the 15 Trycycler assemblies.

This mini-study only looked at sequence accuracy, but Trycycler can be beneficial for other reasons as well. It can help guard against the inclusion of spurious contigs and the exclusion of genuine replicons. It can also let you subjectively see how assemblable your read set is, i.e. whether or not you need longer/deeper/better reads. So I recommend that you use Trycycler whenever you need the best possible long-read bacterial genome assembly. In less important cases or when you need a fully automated assembly, Flye is a good choice.

Appendix: sequence heterogeneity

This mini-study also demonstrated a frustrating challenge that can interfere with bacterial whole-genome assembly: heterogeneity. Sometimes there is not one correct underlying genome but a mixture of multiple underlying genomes. When this happens, the ‘correct’ assembly can be ambiguous.

The genome I used here suffered from this problem. It had a 297 bp ‘flippy’ sequence (a fim switch, read more here and here). Sometimes the genome looked like this:

leading-sequence -> flippy-297-bp-sequence -> trailing-sequence

And sometimes it looked like this:

leading-sequence -> reverse-complement-of-flippy-297-bp-sequence -> trailing-sequence

I’m not sure if this sequence flipped once early in the bacteria’s growth or whether it flipped back and forth many times.

Since the long reads contained a mixture of these two variants, assemblers and polishers got confused. They usually produced an assembly with either one version or the other, but sometimes produced an assembly that was a muddled combination of the two. Trycycler does not necessarily fix problems like this, as it assumes you are assembling a single unambiguous genome.

For my analysis, I masked the problem by ignoring any assembly errors in a 1 kbp window centred on this flippy sequence, so the results shown above are not affected. But I’m bothered by the fact that complications of this type are difficult to spot. I only caught it in this genome because I was doing an in-depth analysis and noticed that errors tended to cluster in one particular region.

I’m not sure what the best solution is for problems like these, but I suspect metagenomics can help. Metagenome assembly is hard because it has to deal with the possibility of strain mixtures, and you can think of sequence heterogeneity in an isolate as being a type of strain mixture. So perhaps we should be treating every genome as if it’s a metagenome. I look forward to seeing what the future holds for long-read metagenome assembly.